Wendell Parris: The Life of an Activist

By Keaton Drennan, Summer 2025 Genealogical Research Intern

Wendell Alexander Parris was born in 1911 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to James Thomas Parris and Lillian Lewis. He grew up in Westmoreland, Pennsylvania, and eventually relocated to Washington, D.C., where he would become an outstanding advocate for his family and community. Wendell’s story, alongside the stories of other descendants of the Parris-Cox line from Menokin, represents the multifaceted outreach and influence that descendants have had within their respective communities.

Wendell Parris spoke out against race bias, served as Director of Boys’ Physical Education for the District’s public schools, served on the District Commissioners Youth Council, and worked as the coach of Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C.--- leading a very respectable career in Physical and Health Education and advocacy.

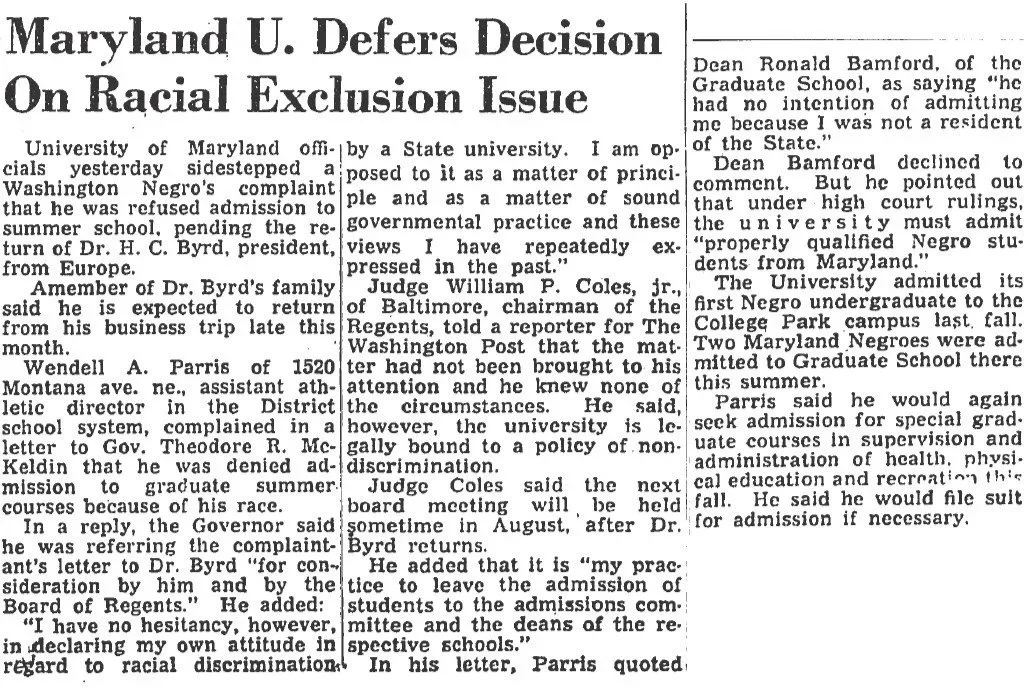

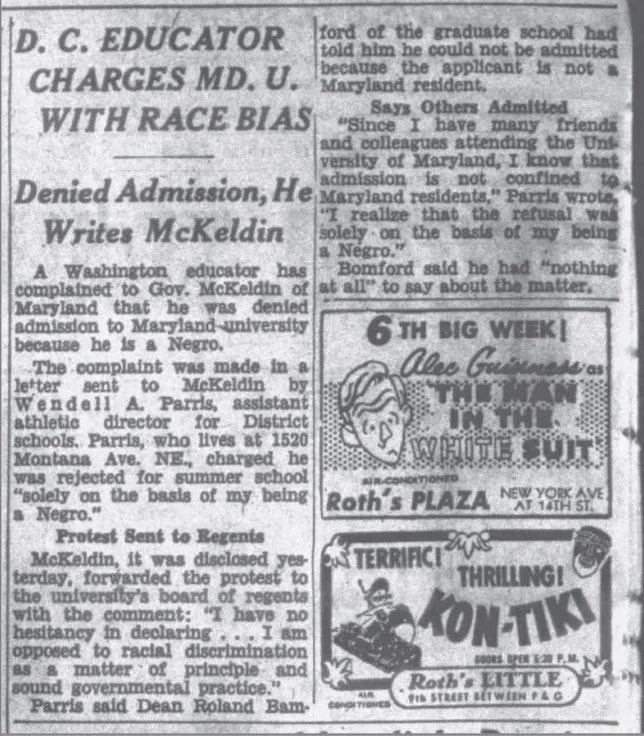

Parris graduated from Howard University in 1936 with a Bachelor of Science in Education alongside 243 graduates. During his life, Parris was a well-rounded and knowledgeable person who valued education and mentored others, as exemplified in his roles as Assistant Athletic Director for District Schools, Coach at Dunbar High School, and Director of the Department of Health, Physical Education, Athletics, and Safety for D.C. public schools. His value for education was also evident in his fight against race bias in the provision of educational opportunities. In 1952, Wendell Parris applied to a graduate program at the University of Maryland and, according to a complaint he made to Governor McKeldin at the time, he was denied admission on account of his race. Parris protested the decision, “Since I have many friends and colleagues attending the University of Maryland, I know that admission is not confined to Maryland residents… I realize that the refusal was solely based on my being a Negro.” After the decision, Parris claimed he would again apply for the University of Maryland’s graduate courses in supervision and administration of health, physical recreation and health for the fall term.

Previously, in 1948, President H. C. Byrd of the University of Maryland encouraged the implementation of legislation in the Maryland State Legislature to establish higher education programs for black persons. Under a proposal submitted to the legislature, the university included recommendations for the attendance of black students for undergraduate programs at Morgan State College and Princess Anne State College under the supervision of regents from the university. Other recommendations included the formation of an advisory board and the gradual integration of black students into graduate programs at College Park. Whether or not the University of Maryland's promises of integration and admission for all students, regardless of race, were kept during Wendell’s admission application, however, is a separate issue.

He publicly exposed racial discrimination, taking matters of race bias to the newspapers. In 1962, Wendell wrote on the challenges that his son faced in applying for jobs because of racial prejudice. His appeals to the newspapers enabled his son to find employment with the Inter-American Development Bank. He was committed to speaking up for what was right while also promoting the needs of others. His narrative aligns with others who chose to publicly call attention to discrimination during the Civil Rights protests in the 1950s and 1960s.

A year after Wendell publicly wrote about the challenges his son faced in searching for employment in Washington, D.C., several Civil Rights groups gathered for the March on Washington in August 1963, marking the culmination of civil rights demonstrations conducted throughout the country. Representatives from these groups, including A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King Jr., and John Lewis, provided orations naming the demands for civil rights legislation and federal action. Wendell Parris’s feelings and actions aligned with those of other civil rights activists, including those from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Congress of Racial Equality, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

-

“U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com: downloaded 17 July 2025, Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 176, Wendall Parris, Washington, D.C.; citing “National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards For District of Columbia, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947.”

“1930 United States Federal Census,” database with images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com: downloaded 13 June 2025), Page: 4B; Enumeration District: 0040; FHL microfilm: 2341890, Wendell A. Parris, Greensburg, Westmoreland, Pennsylvania; citing “National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.”

“Appointed,” The Washington Daily News, October 6, 1965, 12; “Pigskin Club Aids Worthy Causes,” Washington Afro American, November 8, 1958, 13; “Bits Here and There,” The Daily Courier, September 16, 1946, 5.

“Howard Degrees Given Graduates,” Evening Star, June 6, 1936, 6.

“D.C. Educator Charges MD. U. with Race Bias,” Times Herald, July 8, 1952, 18.

“Maryland U. Defers Decision on Racial Exclusion Issue,” The Washington Post, July 9, 1952, 21.

“Byrd Urges Law to Admit Negroes at College Park,” "The Washington Post, November 19, 1948, 1; “Dr. Byrd Acts On Negro Issue,” The Washignton Post, November 19, 1948, 1.

Clayborne Carson, “March on Washington,” in In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s, (Harvard University Press, 1995), 91-94.

“The Historical Legacy of the March on Washington, “ National Museum of African American History & Culture, accessed July 25, 2025, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/historical-legacy-march-washington.

-

Keaton Drennan is a senior at the College of William & Mary studying government and history.

Learn more here.