Self-emancipation refers to the act of freeing oneself from enslavement.

That definition has been expanded upon to include the many forms in which people in the Northern Neck resisted the systems that sought to control their lives during this period in time.

In May of 1776, Bristol (aka Brister/Bristow), along with several other enslaved individuals, fled from Lancaster County in an attempt to meet with Lord Dunmore’s fleet at Gwynn Island. Bristol took his enslaver’s yawl to escape by the water to reach his destination. He and the others who accompanied him were ultimately apprehended by the Patriots.

Bristol was forced to work at Chiswell’s lead mines, located in present-day Wythe County, mining the lead used to create bullets for the American cause. Being sent to the mines served as punishment to any enslaved person who sought freedom with the British. Bristol’s last known whereabouts after the war are from the Virginia Gazette newspaper rewarding twenty pounds for his and another enslaved man’s, Caesar, recapture in 1785. It’s currently unknown whether they were ever recaptured.

Chiswell’s mines were noted by Thomas Jefferson as being of “an object of vast importance” and “perhaps the sole means of supporting the American cause.”

“Twenty Pounds Reward” Virginia Gazette (May 14, 1785)

Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation

“Flight of Lord Dunmore” (1907)

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

“And I do hereby farther declare all indented servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to rebels) free, that are able and willing to bear arms, they joining his Majesty’s troops, as soon as may be, for the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper sense of their duty, to his Majesty’s crown and dignity.”

—John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore and Virginia’s royal governor (Nov. 7, 1775)

After an attempt to exert British control over the Virginia colony backfired, Lord Dunmore issued his 1775 proclamation declaring martial law and offering freedom to any indentured servants and enslaved people who’d aid the British in suppressing the Patriot rebellion. This proclamation was only meant for men willing to bear arms against the Patriots, but British troops were also met with entire families seeking an escape from enslavement.

The Proclamation for them was a promise of freedom, some viewing Lord Dunmore and the British monarchy as liberators and the Patriots as their enemies.

Click on the Images to expand

A Warning

“But should there be any amongst the negroes weak enough to believe that lord Dunmore intends to do them a kindness, and wicked enough to provoke the fury of the Americans against their defenceless father and mothers, their wives, their women and children, let them only consider the difficulty of effecting their escape, and what they must expect to suffer if they fall into the hands of the Americans.”

This excerpt from the Virginia Gazette newspaper comes from a larger declaration by an American colonist addressing Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, warning enslaved people who may consider going to the British. Harm against themselves and loved ones was a real threat to consider. Freedom was not a guarantee.

Wartime Freedom Seekers

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued in 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln, was significant in that it acknowledged that the Civil War was not solely about state reunification, but also about how heavily the Confederacy relied on enslaved labor to function as a nation. Enslaved people had already taken the initiative to deprive the Confederacy of their labor during the war, and Lincoln used this to the Union’s advantage.

Menokin Connections

Daniel West Gordon and Richard Gaines were both enslaved at Menokin. They made the decision to run away on separate occasions during the Civil War, Daniel being 18 at the time and Richard 23. As a free man after the war, Daniel returned to Menokin to work as a tenant farmer, but Richard’s later whereabouts are currently inconclusive.

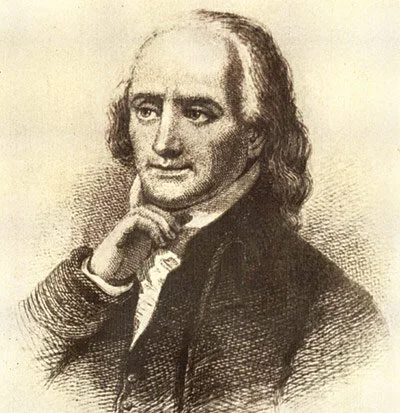

Francis Lightfoot Lee

The Quiet Revolutionary

Francis Lightfoot Lee was a staunch patriot. His contributions during the American Revolution in comparison to the more well-known Founding Fathers may seem understated, but Lee often considered methods for securing freedom that may have been overlooked by others. Americans’ independence occurred in juxtaposition to their enslavement of African Americans whose labor built the nation.

The path towards independence was multifaceted for many, and Francis Lightfoot Lee’s path was one of self-reliance and maintaining a measured front in the face of adversity.

Declaration of Independence

Francis Lightfoot Lee and his brother Richard Henry Lee, alongside 54 other delegates, signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. This document formally signified the independence of the American colonies from British control. It outlined the grievances of the colonists, and promoted ideas that all men are created equal, maintain certain unalienable rights, and that governments derive their power from the consent of the governed. This document stipulated that it is the duty of the individuals reduced to despotism under tyranny to “...throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security”.

Self Emancipatory Actions

Francis Lightfoot Lee’s response to the increasing abuses of power by Great Britain came in the form of boycotts and promotion of American economic independence.

In 1777, Lee urged his fellow Americans to become more self- sufficient by producing their own goods, such as sugar and rum, rather than importing them from the British. Beyond the signing of the Declaration, he contributed greatly to the sustainability of the war effort and life in the Northern Neck. Lee believed the use of militia forces to be insufficient to the cause, and called for the establishment of larger forces and supplemental provisions before the Board of War. In December of 1777, he personally appealed to the governor of Maryland to quickly supply the Continental Army.

Lee’s promotion of colony-made goods, and his urging those with the resources to begin casting guns exemplifies his desire to rid the colonies of British economic domination.

The Silas Deane Affair

During the American Revolution, factional conflict could deeply divide colonial representatives serving in the Continental Congress, making it difficult for political leaders to remain above the fray. Perhaps no episode better illustrates the corrosive power of a public smear campaign than the Silas Deane affair (1778-79). After being accused by Arthur Lee of embezzlement, Deane faced possible recall as an American diplomat to France. Rather than submit to a private inquiry before Congress, Deane took his case to the press, attacking not only Arthur Lee but also William Lee and other diplomats.

You can learn more about Francis Lightfoot Lee’s involvement here.

Post-Revolution Freedom

Approximately 500 enslaved Virginians won their freedom through fighting for the Patriots in the Revolutionary War, but the war didn’t end slavery. The free black population was met with restricted liberties, denying them the rights white citizens naturally possessed. Black loyalists, some of whom came from the Northern Neck, fled the United States to settlements in Nova Scotia for fear of retribution such as re-enslavement or even death. The American Patriots’ victory provided newfound freedom for some while denying the freedom of others, but the journey towards independence didn’t stop after the war.

Peter Harding fled from enslavement in Northumberland County to Nova Scotia, boarding the L’Abondance in 1783. He was accompanied by his wife Kate (or Catharine) Harding, from Gloucester County, and child, Ebenezer, age 2 1⁄2. Ebenezer was born free within British lines.

The Hardings settled in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, where Peter’s occupation is listed as a laborer. Typical work as a laborer would include clearing land, woodcutting, and hunting.

“This given under my hand on this 7th of December 1801...my negro woman Jenny shall be at liberty from the time of my life until Death...” —The will of John Carroll, 1801

This will, written by John Carroll, was meant to free Jenny upon his death. In fact, Jenny was re-enslaved where she faced a variety of abuses. Jenny sued in forma pauperis and used Carroll’s will as evidence against her unlawful enslavement. This resulted in the court granting Jenny her freedom.

Utilizing the courts was another avenue for individuals to gain their freedom or other privileges denied to them.

Preserving Familial Bonds & Histories

The aftermath of the Revolutionary War resulted in a newfound nation and reformed laws. These laws increased owners’ rights, allowing them to divide their property to multiple heirs, which meant the division of enslaved families. A post-Revolution America saw an increase in the purchase, rental, and trade of people under bondage, rendering it difficult for mothers, fathers, and children to maintain stable familial connections.

Being able to tell their stories is an act of resistance in itself. Their lives will not be forgotten as long as we continue to explore, engage with and uplift these histories.

Amanda Beverly, Daniel West Gordon, William Parris, and Peter Henry were enslaved at Menokin between 1830-1865 when Richard Harwood owned the Menokin plantation. Through ongoing genealogical work that began in 2018, we’ve been able to connect with their present-day descendants. Their lives and contributions are an integral part of Menokin’s history that we’ll continue to uncover and highlight.

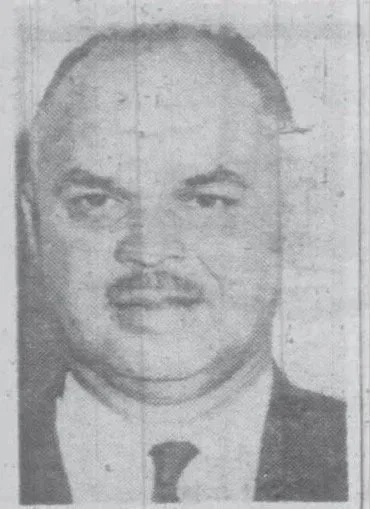

Wendall Parris: The Life of an Activist

A descendant of William Parris, Wendall grew up in Pennsylvania before moving to D.C. He was an advocate for his community challenging racial discrimination which you can learn more about here.